The Flying Dutchman

How KLM lost their most famous captain Parmentier

in a Constellation crash at Prestwick in 1948.

Frank Frazetta

from the Real Free Press Witzend #5

Much of the info below came fromThe Daily Almanac [http://www.dailyalmanacs.com] must have been exaggerating when they said:

Great Mysteries of the Air by Ralph Barker

most interesting book - too bad it's marred by quotes from psychics

"In 1948, Dutch Constellation crashes at Prestwick Scotland (40 murder)".

The facts are sad and dramatic enough, already.

Captain Parmentier

Born Amsterdam, 1904. Joined Fokker in 1920, from there to Dutch Air Force and finally to KLM in 1929. One of the pioneers of the 10,000 mile Amsterdam-Batavia route. With co-pilot J.J. Moll won the 1934 England-Australia handicap with a KLM DC-2 and became one of Holland's popular heroes. Took off from Schiphol Airport in 1940 with a load of important passengers just before the Germans arrived. Was attacked on the Lisboa-London route in a DC-3 by six German Junkers and managed to escape. One of the half-dozen all-time great civil pilots of the world, he had logged over 16,000 hours in 20 years at the time of the Nijmegen crash.

It's all spelled out with much more detail

in Ralph Barker's Great Mysteries of the Air (New York 1967)

chapter 8: A Mistake on a Map.

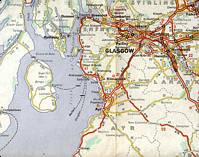

The drama is set at Prestwick

South-West of Glasgow, Scotland.

Under these conditions, in combination with a 20 knot cross-wind on the main runway, KLM-pilots were forbidden to land at Prestwick, instructions drafted by chief pilot Parmentier himself. There were more dangers at Prestwick: Inland of the runway the ground sloped upwards to a height of over 400 feet five miles to the east. Three miles to the north-east the tops of the wireless masts reached almost 600 feet. Three miles inland a high-tension line ran north to south at 450 feet. Parmentier knew Prestwick quite well and himself had written all these hazards up in the KLM route manual.

The routine weather reports, not forecasts, picked up during the flight gave a cloud cover of 700 feet. When Parmentier contacted Prestwick Approach Control by voice radio shortly before 23:00, he still did not know about the forecast drizzle and low cloud base. He also was not aware that the cross wind on the main runway had dropped from 20 to 14 knots, which made it within limits to use without having to land on the shorter Runway 26. Nor was he told that two large SAS airliners had turned back to Copenhagen instead of attempting to land at Prestwick.

Nijmegen route red - power lines orange

click for larger view

Parmentier decided to make a blind approach to the main Runway with a planned overshoot, make a left-handed loop turn to bring him downwind alongside Runway 26 and fly a little beyond it's length before turning again for his final approach. As he expected to be in visual contact, this was less complicated than it may seem.

At 23:16, there was another Morse weather broadcast warning that visibility and cloud ceiling were deteriorating, but as Parmentier and his crew were now in voice radio contact, they missed that one as well. However, they were advised that the cross-wind was within acceptable limits and Parmentier decided to try for a landing on the main runway. But at three miles' distance, he judged that the wind might be too strong and opted for the overshoot and Runway 26 landing. He swept round in a turn over the clearly visible lights of Runway 26, climbed to 450 feet, extended flaps and landing gear and immediately ran into what they judged to be an isolated patch of clouds. In reality, the cloud base now was as low as 300 feet, while Parmentier's own instructions forbade a landing on Runway 26 with clouds below 700 feet.

They were heading straight for the high power lines at two minutes distance. However, their official KLM printed and issued chart showed the highest point of the power lines at 45 instead of 450 feet. Worse, the same map showed no higher ground than 250, not 400 feet and was an invitation to crash into the ground. Near the end of their downwind leg, which they had not bothered to time exactly as they were in visual contact, cloud and fog grew even denser. At this point they should have broken off their attempt and climb out to safety, but they still flew on. According to the map, they made another turn to the left and, coming out of it, hit the power lines, continued to spiral down and finally crashed farther to the East.

The following are the final transmissions between ground control and aircraft.

O'BRIEN (co-pilot): Prestwick Approach Control from Tare Easy Nan. Do you read me? Over.Rescue services did not reach the scene of the crash before 100 minutes had elapsed, and found only six people alive, who all died within 24 hours.

TOWER: Tare Easy Nan from Prestwick Approach Control. Five by five. Over.

Then, the lights at the airport flickered momentarily as the Constellation hit the 132,000 Volts power lines.

O'BRIEN: We have hit something.

PARMENTIER: Operate fire control.

PARMENTIER: We are climbing.

TOWER: What is your position?

NIJMEGEN: Have you any idea where we are?

The court of enquiry concluded that "a pyramid of circumstances" had produced the tragedy.

To quote Ralph Barker's book:

"First there was the complete absence, in the radio messages and conversations between aircraft and airport, of any reference to a deterioration in the weather. Second was the failure of the crew to employ a timing procedure when flying downwind of the south-west runway—Runway 26. Third was the false and misleading character of the chart in use. It transpired that these charts had been copied from American Air Force maps, which must also have been faulty.Speaking for myself, knowing the Dutch intimately, I can't be so astonished. Maps cost money and when you find American Air Force maps somewhere, it's much cheaper to copy them (and forget about copyright).

The court expressed astonishment that such maps should be based on a foreign authority when detailed and accurate Ordnance Survey maps were available."

Why Parmentier, KLM's Star Pilot, would have been suckered into this trap is another question. One thing is sure, their own chief pilot had never been able to get those maps corrected. Like the court of inquiry, one vainly tries to find a reason that goes beyond: "Cheapskates!" Or much worse.

A final quote from the official report:

The actual chart was recovered in a half burnt and charred condition.

It is a poignant circumstance that while about one-third of the chart was completely burnt, the charring stopped within one-eighth of an inch [three millimeters] from the place where the false marking "45 feet" appears.

In 1954 KLM captain writer Viruly lost Super Constellation Triton at Shannon, Ireland.

The 1957 Neutron crash at Biak, West Papua was a disaster and a disgrace.

How Loftleidir almost killed me.

| Airline Nostalgia Classic Aircraft in Color by Adrian Balch    |

copyright notice

all material on this site, except where noted

copyright © by , curaçao

reproduction in any form for any purpose is prohibited

without prior consent in writing